Did you know that your sinuses produce approximately one liter of mucus daily, yet drainage occurs through openings just 1-3 millimeters wide? The sinuses – air-filled cavities behind your forehead, cheeks, and eyes – connect to your nasal passages through small openings called ostia. When these ostia remain blocked or inflamed, mucus accumulates, creating an environment where bacteria and fungi thrive repeatedly.

Recurrent sinus infections differ from isolated acute sinusitis because they involve structural problems, immune dysfunction, or persistent environmental triggers. While antibiotics clear active infections, they don’t address anatomical blockages, allergic inflammation, or biofilm formation that enable reinfection. Consulting the best ENT Surgeon In Singapore can help identify these root causes through detailed imaging and targeted treatment plans, ensuring long-term relief rather than temporary recovery.

Anatomical Factors That Trap Infections

Your sinus anatomy directly influences drainage patterns and infection risk. A deviated nasal septum shifts the wall between your nostrils, narrowing one side and disrupting normal airflow. This asymmetry causes mucus to pool in specific areas rather than draining naturally through the ostia. The trapped mucus becomes infected repeatedly, particularly when the deviation blocks the ostiomeatal complex – the drainage pathway for your maxillary and ethmoid sinuses.

Nasal polyps develop as smooth, grape-like growths from chronic inflammation of the sinus lining. These benign masses physically obstruct sinus openings, preventing mucus drainage even between infection episodes. Polyps often grow in clusters, blocking multiple sinuses simultaneously. Their presence creates a self-perpetuating cycle: blocked drainage causes infection, infection triggers inflammation, and inflammation stimulates more polyp growth.

Concha bullosa occurs when the middle turbinate – a curved bone structure inside your nose – contains an air pocket. This enlarged turbinate compresses surrounding structures, narrowing the drainage pathways from your ethmoid and maxillary sinuses. The condition affects drainage, particularly during nasal congestion, when already narrow passages swell further. Some patients have bilateral concha bullosa, doubling their obstruction risk.

Natural variations in sinus size and ostia diameter also influence infection patterns. Hypoplastic (underdeveloped) sinuses have smaller volumes and narrower openings, making complete drainage difficult. Conversely, oversized sinuses may have ostia positioned unfavorably for gravity-assisted drainage when standing or lying down. These anatomical variants often go undetected until CT imaging reveals their contribution to chronic infections.

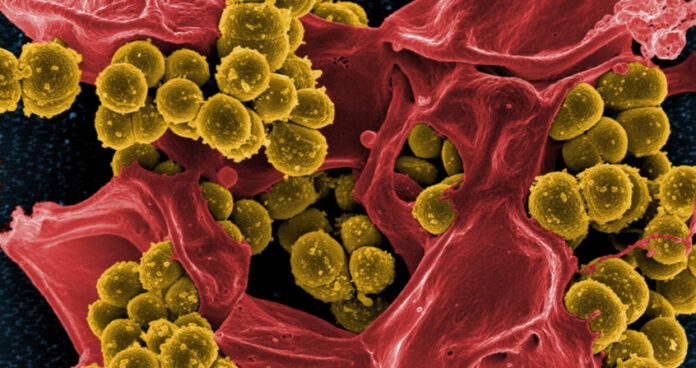

Biofilms and Antibiotic Resistance

Bacterial biofilms transform acute infections into chronic conditions resistant to standard treatments. These microscopic communities form when bacteria attach to your sinus lining and secrete a protective matrix of proteins and sugars. Within this shield, bacteria communicate through chemical signals, share nutrients, and transfer resistance genes between species. The biofilm’s outer layers absorb antibiotics while inner bacteria remain dormant, surviving treatment to reactivate later.

Biofilm bacteria demonstrate significant antibiotic resistance compared to free-floating bacteria. Standard oral antibiotics achieve limited penetration through the biofilm matrix, reaching therapeutic levels only in outer layers. The protected bacteria modify their metabolism, entering slow-growth states that many antibiotics cannot target effectively. When antibiotic pressure diminishes, these dormant cells reactivate, rapidly repopulating the sinuses.

Fungal elements within biofilms add another resistance layer. Fungi like Aspergillus and Candida species integrate into bacterial biofilms, creating polymicrobial communities. These mixed biofilms resist both antibacterial and antifungal medications through cross-protection mechanisms. The fungi provide structural support while bacteria generate defensive enzymes, creating treatment challenges requiring combination therapies.

Breaking established biofilms requires mechanical disruption combined with antimicrobial therapy. Saline irrigations with specific additives like baby shampoo or manuka honey physically disrupt biofilm architecture. Topical antibiotics delivered through irrigation reach higher local concentrations than oral medications. Some ENT specialists use culture-directed antibiotic solutions, selecting medications based on biofilm sampling rather than standard swab cultures.

Environmental and Allergic Triggers

Indoor allergens maintain sinus inflammation between infections, preventing complete healing. Dust mites proliferate in Singapore’s humid climate, with concentrations highest in bedding, carpets, and upholstered furniture. Their microscopic fecal particles trigger allergic responses that swell sinus tissues, narrowing drainage pathways. This allergic inflammation persists even after bacterial infections clear, setting conditions for reinfection.

Mold exposure creates particularly stubborn sinus problems in tropical environments. Airborne mold spores colonize inflamed sinuses, triggering allergic fungal sinusitis in susceptible individuals. Unlike bacterial infections, fungal colonization produces thick, tenacious mucus containing fungal debris and inflammatory cells. This allergic mucin plugs sinus openings completely, requiring mechanical removal beyond standard medical therapy.

Air conditioning systems harbor multiple sinus irritants when poorly maintained. Accumulated dust, mold, and bacteria in filters and ducts circulate throughout indoor spaces. The dry, cooled air itself irritates the nasal passages, reducing ciliary function that normally clears mucus. Temperature transitions between air-conditioned spaces and outdoor humidity trigger vasomotor responses, causing rapid congestion-decongestion cycles that trap secretions.

Chemical irritants in everyday products perpetuate sinus inflammation. Perfumes, cleaning products, and cigarette smoke damage the protective mucus layer and cilia. Paint fumes, new furniture off-gassing, and renovation dust cause acute inflammatory responses lasting weeks. These irritants lower the infection threshold, allowing normally harmless bacteria to establish infections in compromised sinuses.

Immune System Dysfunction

Primary immunodeficiencies predispose certain individuals to recurrent sinus infections despite normal anatomy. Selective IgA deficiency, affecting immunoglobulin A production, compromises the mucous membrane’s first-line defense. Without adequate IgA antibodies in nasal secretions, bacteria adhere more easily to sinus linings. Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) affects multiple antibody types, causing infections throughout the respiratory tract.

Secondary immune compromise from medications or conditions increases infection frequency. Corticosteroids for asthma or autoimmune conditions suppress local immune responses in sinus tissues. Chemotherapy and immunosuppressive drugs for organ transplants eliminate the body’s ability to control bacterial colonization. Diabetes mellitus impairs white blood cell function, slowing the clearance of pathogens from infected sinuses.

Ciliary dysfunction prevents normal mucus clearance regardless of immune competence. Primary ciliary dyskinesia causes defective cilia movement from birth, leading to mucus stagnation throughout the respiratory system. Acquired ciliary damage from viral infections, smoking, or chronic inflammation produces similar effects. Without coordinated ciliary beating, mucus moves too slowly to prevent bacterial overgrowth.

Nutritional deficiencies subtly impair immune function and tissue healing. Vitamin D deficiency reduces antimicrobial peptide production in sinus tissues. Zinc deficiency impairs neutrophil function and antibody production. Iron deficiency, while improving bacterial growth limitation, weakens cellular immunity. These deficiencies often coexist in patients with restricted diets or absorption problems.

Medical Management Strategies

Long-term antibiotic therapy targets biofilm bacteria through sustained drug exposure. Macrolide antibiotics like azithromycin provide anti-inflammatory effects beyond their antimicrobial action. Given at sub-antimicrobial doses for 3-6 months, macrolides reduce mucus production, improve ciliary function, and disrupt bacterial communication within biofilms. This approach particularly benefits patients with concurrent nasal polyps.

Intranasal corticosteroid sprays reduce inflammation when used correctly with specific techniques. Mometasone and fluticasone propionate penetrate deeper into sinus cavities than older preparations. The “Mygind position” – lying supine with head tilted back and turned toward the affected side – improves medication delivery to the middle meatus. Corticosteroid irrigations deliver higher doses directly to polyps and inflamed tissues, though requiring special preparation.

Saline irrigation modifications enhance mucus clearance and biofilm disruption. Hypertonic saline (2-3% salt concentration) draws fluid from swollen tissues while creating an inhospitable environment for bacteria. Adding xylitol to irrigations reduces bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. Manuka honey solutions provide antimicrobial effects against resistant organisms. Temperature matters – body-temperature irrigations cause less reflex congestion than cold solutions.

Antihistamine selection depends on specific allergic triggers and symptom patterns. Second-generation antihistamines like cetirizine and loratadine reduce allergic inflammation without causing drowsiness. Intranasal antihistamines provide rapid local relief for allergic rhinitis contributing to sinusitis. Leukotriene antagonists like montelukast address both allergic inflammation and nasal polyp growth in aspirin-sensitive patients.

Conclusion

Recurrent sinus infections stem from correctable underlying causes, including anatomical obstruction, biofilm colonization, and allergic inflammation. Daily saline irrigations, environmental modifications, and targeted medical therapy break the infection cycle. Advanced diagnostic imaging and surgical options restore normal sinus function when conservative treatment fails.

If you are experiencing recurring sinus infections, facial pain, or nasal congestion despite multiple antibiotic courses, an ENT specialist can identify underlying causes and develop a comprehensive treatment plan.